-40%

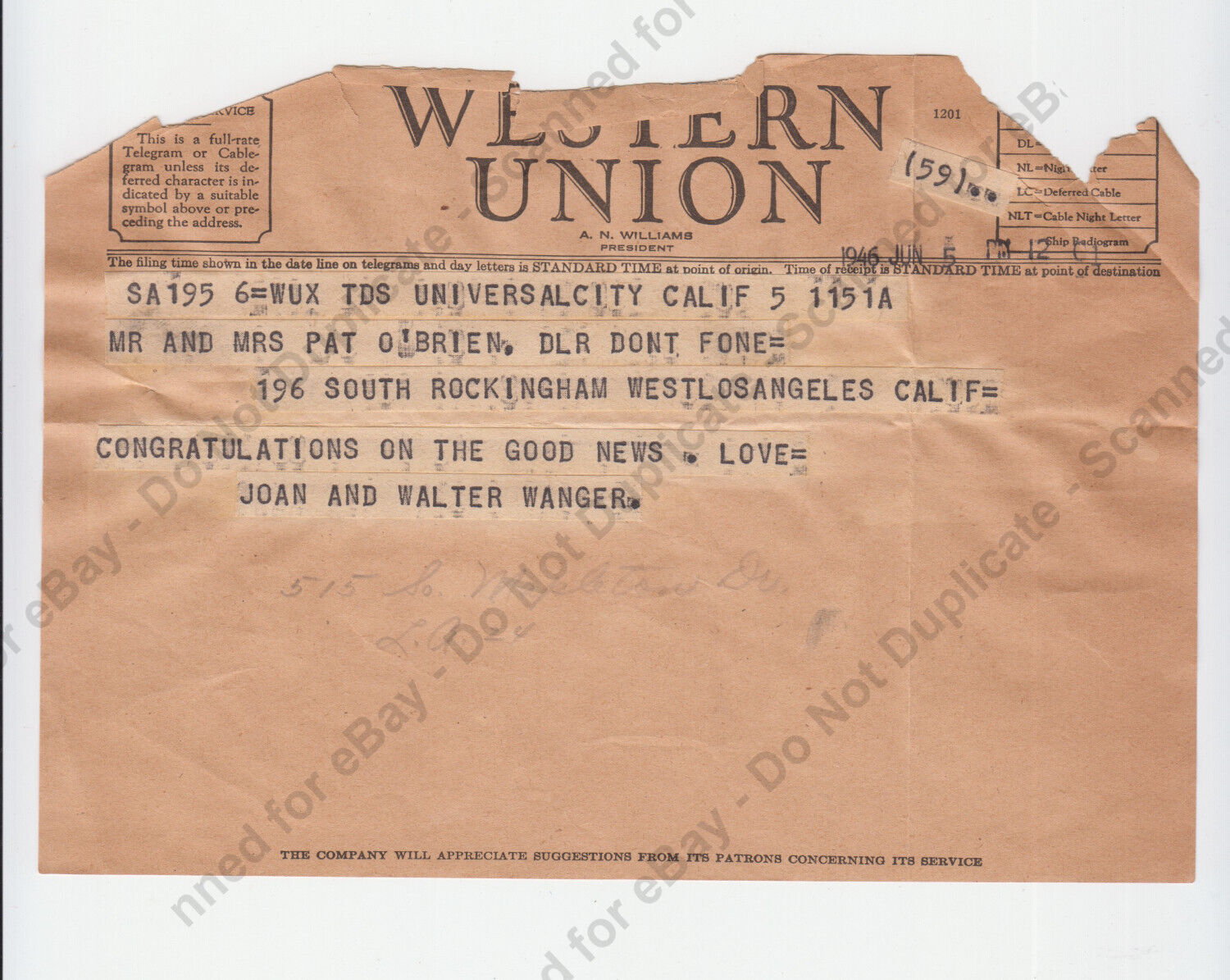

Joan Bennett / Walter Wanger Western Union telegram 1946 to Mrs. Pat O’Brien

$ 15.83

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Joan Bennett / Walter Wanger Western Union telegram 1946 to Mrs. Pat O’BrienSize: 8” X 5 ½” / Unique Characteristics: Date stamped “1946 JUN 5 PM 12 01” Signed “Love / Joan and Walter Wanger” (address 515 So. Mapleton Dr. / L.A. 24”’ penciled-in by recipient Eloise O’Brien).

I've never believed in collecting for it's own sake. Collectors items should be shared and circulated. I grew up among my entertainment heroes of the Golden Age of Hollywood, and am now selling-off some of the treasures I accumulated as a fortunate young man in 1970s Tinsel Town.

The items I'm selling here have never been on the market before.

Joan Bennett

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Joan Geraldine Bennett (February 27, 1910 – December 7, 1990) was an American stage, film, and television actress. She came from a show-business family, one of three acting sisters. Beginning her career on the stage, Bennett appeared in more than 70 films from the era of silent films, well into the sound era. She is best remembered for her film noir femme fatale roles in director Fritz Lang's films—including Man Hunt (1941), The Woman in the Window (1944) and Scarlet Street (1945)—and for her television role as matriarch Elizabeth Collins Stoddard (and ancestors Naomi Collins, Judith Collins, and Flora Collins PT) in the gothic 1960s soap opera Dark Shadows, for which she received an Emmy nomination in 1968.

Bennett's career had three distinct phases: first as a winsome blonde ingenue, then as a sensuous brunette femme fatale (with looks that movie magazines often compared to those of Hedy Lamarr), and finally as a warmhearted wife-and-mother figure.

In 1951, Bennett's screen career was marred by scandal after her third husband, film producer Walter Wanger, shot and injured her agent Jennings Lang. Wanger suspected that Lang and she were having an affair, a charge which Bennett adamantly denied. She married four times.

For her final film role, as Madame Blanc in Dario Argento's cult horror film Suspiria (1977), she received a Saturn Award nomination.

Early life

Joan Geraldine Bennett was born in the Palisade section of Fort Lee, New Jersey, on February 27, 1910, the youngest of three daughters of actor Richard Bennett and actress/literary agent Adrienne Morrison. Her elder sisters were actress Constance Bennett and actress/dancer Barbara Bennett, who was the first wife of singer Morton Downey and the mother of Morton Downey Jr. Part of a famous theatrical family, Bennett's maternal grandfather was Jamaica-born Shakespearean actor Lewis Morrison, who embarked on a stage career in the late 1860s. He was of English, Spanish, Jewish, and African ancestry. On the side of her maternal grandmother, actress Rose Wood, the profession dated back to traveling minstrels in 18th-century England.

Bennett first appeared in a silent movie as a child with her parents and sisters in her father's drama The Valley of Decision (1916), which he adapted for the screen. She attended Miss Hopkins School for Girls in Manhattan, then St. Margaret's, a boarding school in Waterbury, Connecticut, and L'Hermitage, a finishing school in Versailles, France.

On September 15, 1926, 16-year-old Bennett married John M. Fox in London. They divorced in Los Angeles on July 30, 1928, based on charges of his alcoholism. They had one child, Adrienne Ralston Fox (born February 20, 1928), for whom Bennett fought successfully in court to rename Diana Bennett Markey, when the child was eight years old. Her name changed to Diana Bennett Wanger in 1944.

Career

Bennett's stage debut was at the age of 18, acting with her father in Jarnegan (1928), which ran on Broadway for 136 performances and for which she received good reviews. By the time she turned 20 she had become a movie star through such roles as Phyllis Benton in Bulldog Drummond starring Ronald Colman, which was her first important role, and Lady Clarissa Pevensey opposite George Arliss in Disraeli (both 1929).

She moved quickly from movie to movie throughout the 1930s. Bennett appeared as a blonde (her natural hair color) for several years. She starred in the role of Dolores Fenton in the United Artists musical Puttin' On The Ritz (1930) opposite Harry Richman and as Faith Mapple, his beloved, opposite John Barrymore in an early sound version of Moby Dick (1930) at Warner Brothers.

Under contract to Fox Film Corporation, she appeared in several movies. Receiving top billing, she played the role of Jane Miller opposite Spencer Tracy in She Wanted a Millionaire (1932). She was billed second, after Tracy, for her role as Helen Riley, a personable waitress who trades wisecracks, in Me and My Gal (1932).

On March 16, 1932, she married screenwriter/film producer Gene Markey in Los Angeles,[10] but the couple divorced in Los Angeles on June 3, 1937. They had one child, Melinda Markey (born February 27, 1934, on Bennett's 24th birthday).

Bennett left Fox to play Amy, a pert sister competing with Katharine Hepburn's Jo in Little Women (1933), which was directed by George Cukor for RKO. This movie brought Bennett to the attention of independent film producer Walter Wanger, who signed her to a contract and began managing her career. She played the role of Sally MacGregor, a psychiatrist's young wife slipping into insanity, in Private Worlds (1935) with Joel McCrea. Bennett starred in the film Vogues of 1938 (1937), including the title sequence, in which she donned a diamond-and-platinum bracelet set with the Star of Burma ruby. Wanger and director Tay Garnett persuaded her to change her hair from blonde to brunette as part of the plot for her role as Kay Kerrigan in the scenic Trade Winds (1938) opposite Fredric March.

With her change in appearance, Bennett began an entirely new screen career as her persona evolved into that of a glamorous, seductive femme fatale. She played the role of Princess Maria Theresa in The Man in the Iron Mask (1939) opposite Louis Hayward, and the role of the Grand Duchess Zona of Lichtenburg in The Son of Monte Cristo (1940) opposite Hayward.

During the search for an actress to play Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind, Bennett was given a screen test and impressed producer David O. Selznick to such an extent that she was one of the final four actresses, along with Jean Arthur, Vivien Leigh and Paulette Goddard.

Bennett in the trailer for The Woman in the Window (1944)

On January 12, 1940, Bennett and producer Walter Wanger were married in Phoenix, Arizona. They were divorced in September 1965 in Mexico. The couple had two children together, Stephanie Wanger (born June 26, 1943) and Shelley Wanger (born July 4, 1948). The following year, on March 13, 1949, Bennett became a grandmother at the age of 39.

Combined with her sultry eyes and husky voice, Bennett's new brunette look gave her an earthier, more arresting persona. She won praise for her performances as Brenda Bentley in The House Across the Bay (1940), also featuring George Raft, and as Carol Hoffman in the anti-Nazi drama The Man I Married, a film in which Francis Lederer also starred.

She then appeared in a sequence of highly regarded film noir thrillers directed by Fritz Lang, with whom she and Wanger formed their own production company. Bennett appeared in four movies under Lang's direction, including as Cockney Jerry Stokes in Man Hunt (1941) opposite Walter Pidgeon, as mysterious model Alice Reed in The Woman in the Window (1944) with Edward G. Robinson, and as vulgar blackmailer Katharine "Kitty" March in Scarlet Street (1945), another film with Robinson.

Bennett was the shrewish, cuckolding wife, Margaret Macomber, in Zoltan Korda's The Macomber Affair (1947) opposite Gregory Peck, as the deceitful wife, Peggy, in Jean Renoir's The Woman on the Beach (also 1947) opposite Robert Ryan and Charles Bickford, and as tormented Lucia Harper in Max Ophüls' The Reckless Moment (1949) as the victim of a blackmailer played by James Mason. Then, easily shifting images again, she changed her screen persona to that of an elegant, witty and nurturing wife and mother in two comedies directed by Vincente Minnelli.

Playing the role of Ellie Banks, the wife of Spencer Tracy and mother of Elizabeth Taylor, Bennett appeared in both Father of the Bride (1950) and Father's Little Dividend (1951).

She made a number of radio appearances from the 1930s to the 1950s, performing on such programs as The Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy Show, Duffy's Tavern, The Jack Benny Program, Ford Theater, Suspense and the anthology series Lux Radio Theater and Screen Guild Theater.

With the increasing popularity of television, Bennett made five guest appearances in 1951, including an episode of Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca's Your Show of Shows.

Political views

She was a very active member of both the Hollywood Democratic Committee and The Hollywood Anti-Nazi League and donated her time and money to many liberal causes (such as the Civil Rights Movement) and political candidates (including Franklin D. Roosevelt, Henry A. Wallace, Adlai Stevenson II, John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Jimmy Carter) during her lifetime.

Scandal

For 12 years Bennett was represented by agent Jennings Lang, the onetime vice-president of the Sam Jaffe Agency, who then headed MCA's West Coast television operations. She and Lang met on the afternoon of December 13, 1951, to talk over an upcoming TV show.

Bennett parked her Cadillac convertible in the lot at the back of the MCA offices, at Santa Monica Boulevard and Rexford Drive, across the street from the Beverly Hills Police Department, and she and Lang drove off in his car. Meanwhile, her husband Walter Wanger drove past about 2:30 p.m. and noticed his wife's car parked there. Half-an-hour later, he again saw her car there and stopped to wait. Bennett and Lang drove into the parking lot a few hours later and he walked her to her convertible. As she started the engine, turned on the headlights, and prepared to drive away, Lang leaned on the car, with both hands raised to his shoulders, and talked to her.

In a fit of jealousy, Wanger walked up and twice shot and wounded the unsuspecting agent. One bullet hit Jennings in the right thigh, near the hip, and the other penetrated his groin. Bennett said she did not see Wanger at first. She said she suddenly saw two vivid flashes, then Lang slumped to the ground. As soon as she recognized who had fired the shots, she told Wanger, "Get away and leave us alone." He tossed the pistol into his wife's car.

She and the parking lot's service station manager took Lang to the agent's doctor. He was then taken to a hospital, where he recovered. The police station was located across the lot, officers had heard the shots, and came to the scene and found the gun in Bennett's car when they took Wanger into custody. Wanger was booked and fingerprinted, and underwent lengthy questioning.

"I shot him because I thought he was breaking up my home," Wanger told the chief of police of Beverly Hills. He was booked on suspicion of assault with intent to commit murder. Bennett denied a romance. "But if Walter thinks the relationships between Mr. Lang and myself are romantic or anything but strictly business, he is wrong," she declared. She blamed the trouble on financial setbacks involving film productions Wanger was involved with, and said he was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. The following day Wanger, out on bond, returned to their Holmby Hills home, collected his belongings and moved out. Bennett, however, said there would not be a divorce.

On December 14, Bennett issued a statement in which she said she hoped her husband "will not be blamed too much" for wounding her agent. She read the prepared statement in the bedroom of her home to a group of newspapermen while TV cameras recorded the scene.

Wanger's attorney Jerry Giesler mounted a "temporary insanity" defense. He then decided to waive his right to a jury, and threw himself on the mercy of the court. Wanger served a four-month sentence in the County Honor Farm at Castaic, California, 39 miles north of Downtown Los Angeles, quickly returning to his career to make a series of successful films.

Meanwhile, Bennett went to Chicago to appear on the stage in the role as the young witch Gillian Holroyd in Bell, Book, and Candle, then went on national tour with the production.

She made only five movies in the decade that followed the 1951 shooting incident, and only two films in the 1970s, for the incident was a stain on her career and she became virtually blacklisted. Blaming the scandal that occurred for destroying her career in the motion picture industry, Bennett once said, "I might as well have pulled the trigger myself." Although Humphrey Bogart, a longtime friend, pleaded with Paramount Pictures on her behalf to keep her after her role as Amelie Ducotel in We're No Angels (1955), the studio refused.

As the movie offers dwindled after the scandal, Bennett continued touring in stage successes, such as Susan and God, Once More, with Feeling, The Pleasure of His Company and Never Too Late. Her next TV appearance was in the role of Bettina Blane in an episode of General Electric Theater in 1954. Other roles included Honora in Climax! (1955) and Vickie Maxwell in Playhouse 90 (1957). In 1958, she appeared as the mother in the short-lived television comedy/drama Too Young to Go Steady to teenagers played by Brigid Bazlen and Martin Huston.

She starred on Broadway in the comedy Love Me Little (1958), which ran for only eight performances.

Of the scandal, in a 1981 interview, Bennett contrasted the judgmental 1950s with the sensation-crazed 1970s and 1980s. "It would never happen that way today," she said, laughing. "If it happened today, I'd be a sensation. I'd be wanted by all studios for all pictures."

Later years

Despite the shooting scandal and the damage it caused Bennett's film career, she and Wanger remained married until 1965. She continued to work steadily on the stage and in television, including a guest role as Denise Mitchell in an episode of TV's Burke's Law (1965).

Bennett in the TV series Dark Shadows

Bennett received star billing in the gothic soap opera Dark Shadows for its entire five-year run, 1966 to 1971, receiving an Emmy Award nomination in 1968 for her performance as Elizabeth Collins Stoddard, mistress of the haunted Collinwood Mansion. Her other roles in Dark Shadows were Naomi Collins, Judith Collins Trask, Elizabeth Collins Stoddard PT (parallel time, as the show described its alternate reality), Flora Collins, and Flora Collins PT. In 1970, she appeared as Elizabeth in House of Dark Shadows, the feature film adaptation of the series. However, she declined to appear in the sequel Night of Dark Shadows, and her character Elizabeth was mentioned therein as being recently deceased.

Her autobiography The Bennett Playbill, written with Lois Kibbee, was published in 1970.

Her other TV guest appearances include Bennett's roles as Joan Darlene Delaney in an episode of The Governor & J.J. (1970) and as Edith in an episode of Love, American Style (1971). She starred in five made-for-TV movies between 1972 and 1982.

Bennett also appeared in one more feature film, as Madame Blanc in director Dario Argento's horror film Suspiria (1977), for which she received a 1978 Saturn Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress.

Bennett and retired publisher/movie critic David Wilde were married on February 14, 1978, 13 days before her 68th birthday, in White Plains, New York. Their marriage lasted until her death in 1990.

Bennett's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6300 Hollywood Blvd

Celebrated for not taking herself too seriously, Bennett said in a 1986 interview, "I don't think much of most of the films I made, but being a movie star was something I liked very much."

Bennett has a motion pictures star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for her contributions to the film industry. Her star is located at 6300 Hollywood Boulevard, a short distance from the star of her sister Constance.

Death

Bennett died of heart failure on Friday evening, December 7, 1990, aged 80, at her home in Scarsdale, New York. She is interred in Pleasant View Cemetery, Lyme, Connecticut, with her parents.

Walter Wanger

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Walter Wanger (born Walter Feuchtwanger; July 11, 1894 – November 18, 1968) was an American film producer active from the 1910s, his career concluding with the turbulent production of Cleopatra, his last film, in 1963. He began at Paramount Pictures in the 1920s and eventually worked at virtually every major studio as either a contract producer or an independent. He also served as President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from 1939 to October 1941 and from December 1941 to 1945. Strongly influenced by European films, Wanger developed a reputation as an intellectual and a socially conscious movie executive who produced provocative message movies and glittering romantic melodramas. He achieved notoriety when, in 1951, he shot and wounded the agent of his wife, Joan Bennett, because he suspected they were having an affair. He was convicted of the crime and served a four-month sentence, then returned to making movies.

After his death, his production company, Walter Wanger Productions, was sold to and absorbed by Time-Life Films, which also acquired many films produced by him and that company.

Early life

Wanger was born Walter Feuchtwanger in San Francisco. He was the son of Stella (Stettheimer) and Sigmund Feuchtwanger, who were from German Jewish families that had emigrated to the United States in the nineteenth century. Wanger was from a non-observant Jewish family, and in later life attended Episcopalian services with his wife. In order to assimilate into American society, his mother altered the family name simply to Wanger in 1908. The Wangers were well-connected and upper middle class, something which later differentiated Wanger from the other Jewish film moguls who came from more ordinary backgrounds.

Wanger attended Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, where he developed an interest in amateur theatre. After leaving Dartmouth, Wanger became a professional theatrical producer in New York City where he worked with figures such as the influential British manager Harley Granville-Barker and the Russian actress Alla Nazimova.

Following the American entry into World War I in 1917, Wanger served with the United States Army in Italy initially in the Signal Corps where he worked as a pilot on reconnaissance missions, and later in propaganda operations directed at the Italian public. It was during this period that Wanger first came into contact with filmmaking. In April 1918 Wanger was transferred to the Committee on Public Information, and joined an effort to combat anti-war or pro-German sentiment in Allied Italy. This was partly accomplished through a series of short propaganda films screened in Italian cinemas promoting democracy and Allied war aims.

After the Allied victory, Wanger returned to the United States in 1919 and was discharged from the army. Wanger married silent film actress Justine Johnstone in 1919. He initially returned to theatre production, before a chance meeting with film producer Jesse Lasky drew him into the world of commercial filmmaking. Lasky was impressed with Wanger's ideas and his experiences in the theatre, and hired him to head a New York office vetting and acquiring books and plays for use as film stories for Famous Players-Lasky (later to become Paramount), which was then the largest film production company in the world.

Early career

Wanger's job at Paramount was to help meet the studio's large annual requirement for fresh stories. One of Wanger's major successes in his early years with the company was his identification of the British novel The Sheik as a story with potential. In 1921 it was turned into an extremely successful film starring Rudolph Valentino. The film helped establish the popularity of the Orientalist genre, which Wanger returned to a number of times during his career.

By 1921, Wanger was unhappy with the terms he was receiving and left his job with Paramount. He travelled to Britain where he worked as a prominent cinema and theatre manager until 1924. While on a visit to London, Paramount key founder Jesse Lasky offered to appoint him as "general manager of production" on improved terms and Wanger accepted.

Wanger's second spell with Paramount lasted from 1924 to 1931, during which time his annual wage rose from 0,000 to 0,000. He was tasked with overseeing the work of the studio heads, which meant he had little involvement with the production of individual films. Because he was based in New York, Wanger worked more closely with the company's Astoria Studios in Queens. A rivalry developed between Wanger-influenced Astoria productions and those of B.P. Schulberg who ran the Paramount productions in Hollywood. From the mid-1920s, the company was rapidly overtaken by the recently formed Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as the industry's leading company and this along with heavy losses incurred on big-budget films, led to Paramount's executives decision in 1927 to eventually close the New York operation and shift all production to Hollywood. Wanger opposed this move and felt he was being squeezed out of the company.

In 1926, Warner Brothers premièred Don Juan, a film with music and sound effects, and the following year released The Jazz Singer with dialogue and singing scenes. Along with other big companies, Paramount initially resisted adopting sound films and continued to exclusively make silent ones. Wanger convinced his colleagues of the importance of sound, and personally oversaw the conversion of 1928 silent baseball film Warming Up to sound. The sound version had synchronized music and sound effects without dialogue. After the film's successful release, the company switched dramatically away from silent to sound.

After being closed for a year, the Astoria Studios were re-opened in 1929 to make sound films, taking advantage of their close proximity to Broadway where many actors were recruited to appear in early Talkies. Wanger recruited large numbers of new performers including Maurice Chevalier, the Marx Brothers, Claudette Colbert, Jeanette MacDonald, Fredric March and Miriam Hopkins and directors such as George Cukor and Rouben Mamoulian. Wanger's New York films were often adapted from stage plays and focused on sophisticated comedies, often with European settings, while Schulberg concentrated on more populist stories in Hollywood. As the effects of the Great Depression hit the film industry in the early 1930s, the Astoria Studios increasingly struggled to produce box office hits, and in December 1931 it was closed down again. Wanger had been informed that his contract would not be renewed, and he had already left the company.

Columbia

After leaving Paramount, Wanger tried unsuccessfully to set himself up as an independent. Unable to secure financing for films, he joined Columbia Pictures in December 1931. Wanger was recruited by Harry Cohn, the studio's co-founder, who wanted to move Columbia away from its Poverty Row past by producing several special, large-budget productions each year to complement the bulk of the studio's low-budget films. Wanger was to take on a greater personal role in individual films than he had previously, although he always attempted to give directors and screenwriters creative freedom. In general his efforts were overshadowed by the more successful films made by Frank Capra for the studio.

Later career

Wanger was given an Honorary Academy Award in 1946 for his six years service as president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He refused another honorary Oscar in 1949 for Joan of Arc, out of anger over the fact that the film, which he felt was one of his best, had not been nominated for Best Picture.

His 1958 production of I Want to Live! starred Susan Hayward in an anti-capital punishment film that is one of the more highly regarded films on the subject. Hayward won her only Oscar for her role in the film.

In 1963, Wanger was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture for his production of Cleopatra.

In May 1966, Wanger received the Commendation of the Order of Merit, Italy's third-highest honor, from Consul General Alvaro v. Bettrani, "for your friendship and cooperation with the Italian government in all phases of the motion picture industry."

Personal life and death

Wanger married silent film actress Justine Johnstone in 1919.[citation needed] They divorced in 1938, and in 1940, he married actress Joan Bennett whom he divorced in 1965. They had two daughters, Stephanie (born 1943) and Shelley Antonia (born 1948), and Wanger adopted Bennett's daughter, Diana (born 1928), by her marriage to John Fox.

Wanger died of a heart attack, aged 74, in New York City. He was interred in the Home of Peace Cemetery in Colma, California.